Far Inland

by Peter Urpeth

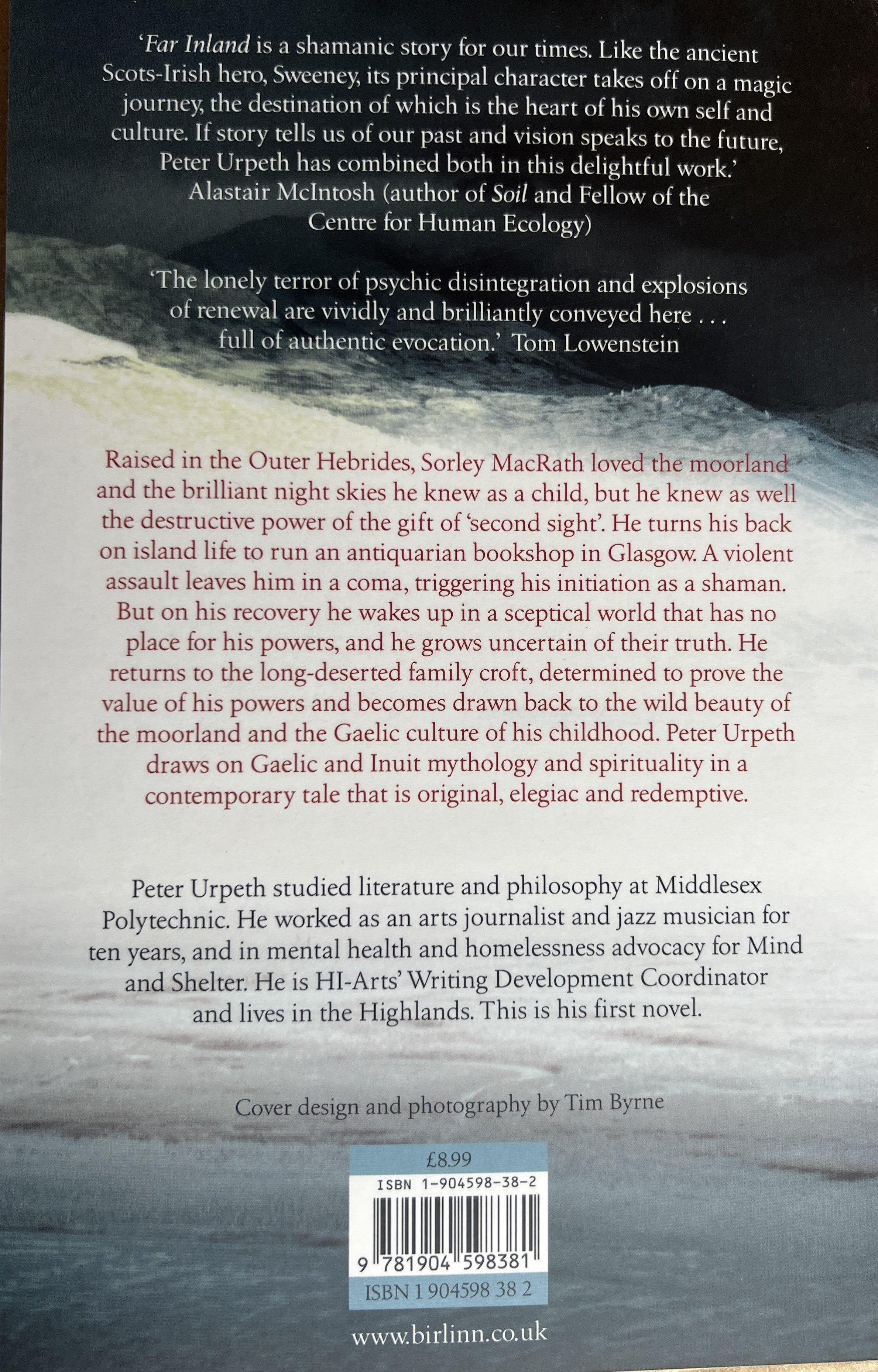

‘Far Inland is a shamanic story for our times. If story tells us of our past and vision speaks to the future, Peter Urpeth has combined both in this delightful work’ – Alastair McIntosh, author of Hell and High Water and fellow of the Centre for Human Ecology

‘The lonely terror of psychic disintegration and explosions of renewal are vividly and brilliantly conveyed here . . . full of authentic evocation’ – Tom Lowenstein, author of Ancient Land, Sacred Whale (Bloomsbury)

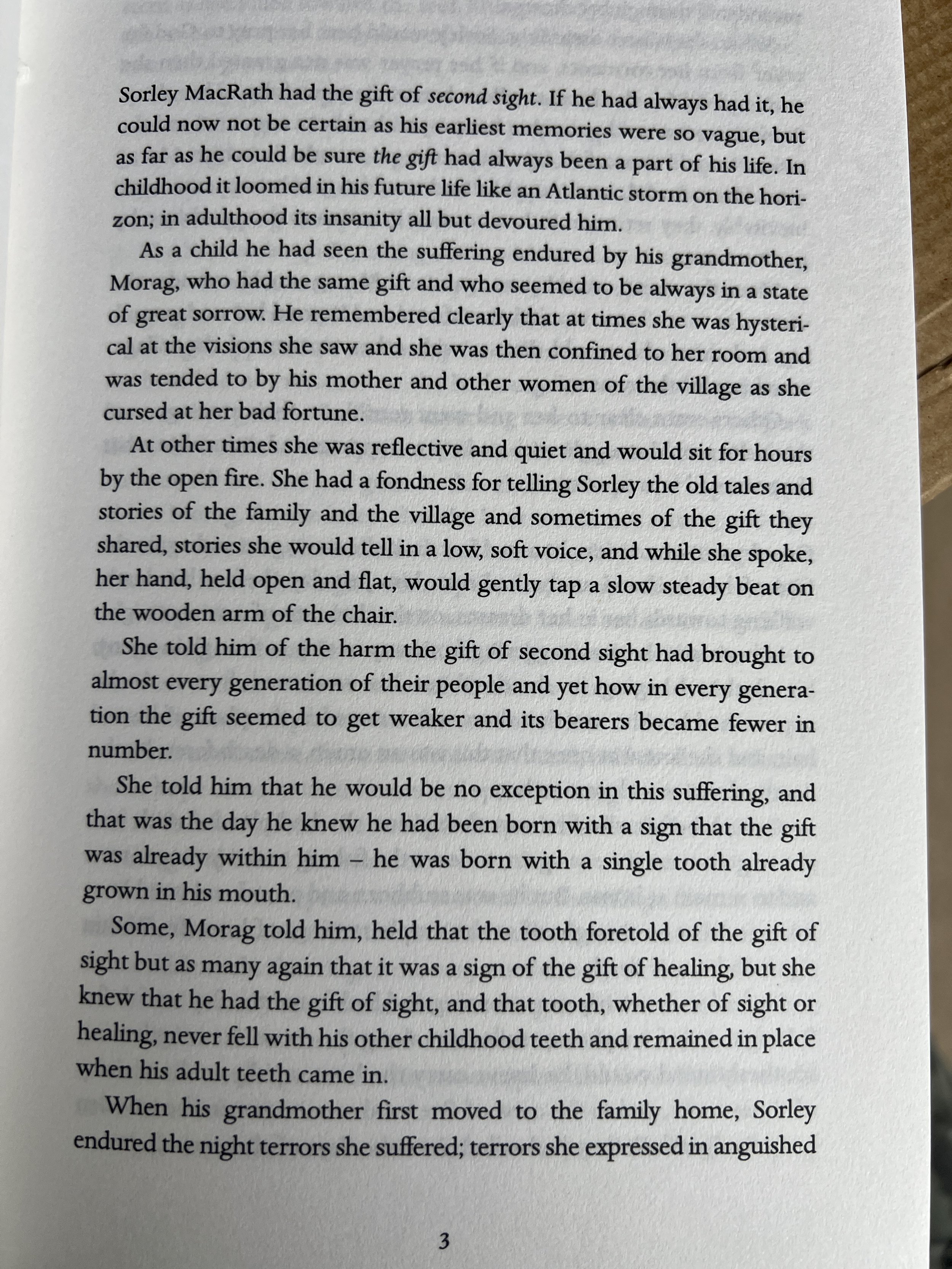

Raised in the Outer Hebrides, Sorley MacRath loved the moorlands and the brilliant night skies he knew as a child. But he knew as well the destructive power of the gift of ’second sight’.

As a young man he turned his back on the island for life in Glasgow where, ultimately, he would run an antiquarian bookshop. But events soon prove to him that his inherited powers are far greater than he knew.

A violent assault leaves him in a coma and triggers his initiation as a shaman through startling encounters with his ancestors, only for him to wake into a sceptical world with no place for his archaic powers, and he too is uncertain of their truth and unskilled in their application. Haunted by memories and loss, he returns to his island home determined to prove the truth in his powers and his worth. There, living in the long-empty family croft house, he is drawn back to the wild beauty of the moorlands and the Gaelic culture of his childhood. Set on the Isle of Lewis and in Glasgow, Far Inland draws on Gaelic and Inuit mythology and spirituality to inform a contemporary tale that is profoundly original, elegiac and redemptive.

I was taken aback by the very first review of Far Inland, when it was published - this by the great author and publisher Martin Goodman -

Review by Martin Goodman - writer (Martin Goodman.com, 2007)

‘Most shamans I've met distrust other shamans. The onetime notion of shamans as nature's bankers, interceding between their population and the natural world so as to know which plants were right for consuming, which animals populations healthy enough to hunt sustainably, has worn threadbare. Their customers seek concoctions to give them victories in love and business, and shamans imbibe the likes of dattura to journey off on life-or-death missions beyond conscious realms in efforts to inflict defeat on rival shamans. My own shamanic book, ‘I Was Carlos Castaneda’, saw me enmeshed in the middle of one such shamanic battle. Shamanism has some romantic allure, but enmeshes participants in such a powerful field of illusions spiked with revelation that they easily become enraptured.

A new Scottish shamanic novel was nestling on a shelf at Foyles bookstore on London's Southbank. The opening page read well, so it travelled home with me. I had always felt shamanism should be as lively a thread in Scotland as it was in Siberia. The village priest in the highland village of Glencoe where I lived for some years felt himself to be surrounded by paganism, but when I was looking for appreciation of the sacredness of mountains, for recognition of mountains as independent beings, I found no active practice of such reverence in the culture.

For his novel Far Inland Peter Urpeth mined Inuit and Gaelic tales. We meet several generations of shamans, ending in present-day Sorley who has left his island home in the Outer Hebrides to run an antiquarian bookstore in the City. A very Scottish tilt sees his shamanic journeys triggered by the intake of massive doses of whisky.

In Peru the trigger was ayahuasca. I suppose you take whatever you can get. The novel is grand at evoking the landscapes and the journeys in crisp and unfussy flights of detail, and has passages of language to delight in. Oddly after reading it I could remember the names of every character in the book, apart from the protagonist.

Names are useful in interaction with other people, but Sorley's progress through the book is away from all such human engagement.

Just as he fled his island family, he ultimately flees his wife in the city to live alone on his island. Shamans cannot survive without understanding is his message, and cannot be understood in the city.

He has moved far enough by the close of the book to realise that his newfound vocation as shaman does not need to be dramatic, it can simply mean entering into the elemental nature of life in solo retreat in his island home. I suspect such revelation is akin to those dewy-eyed moments of lucidity and wonder an alcoholic can encounter between bottles. Can shamanism be transplanted to the city? Perhaps, but I do think it is vital to maintain some connection with the natural world. I find great comfort in writing this piece from back among the rain and wind and sun-swept Pyrenean hills in which much of I was Carlos Castaneda is set. I also think part of the shamanic journey is learning to live in full accord with other humans.

That's also part of the journey of a novel. Far Inland rounds off well enough, but is not as near completion as it believes. I had an engrossing time in the writer's world, so will buy into the sequel if the journey is ever continued.’

An academic reading of Far Inland…

Reviews on Amazon:

5 five star reviews….

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 29 June 2010

An excellent novel, and all the more relevant as I live on the Isle of Lewis. Considered good enough that someone pinched our first copy and this was a replacement!

May 01, 2018 Flora Kennedy said it was amazing

"Far Inland" looks so very modest and unassuming and yet is a powerful, enigmatic and epic story beautifully told. The writing is just sublime; gorgeous and vivid whether the author is communicating the emotions of the characters or the wild landscape of the Outer Hebrides.

Peter Urpeth captures and details for us with poetry and wonderment a pivotal time in Hebridean history, our recent past, when we as indigeneous islanders suddenly found ourselves metaphorically 'far inland'.

The title is a net full of expansive themes both soulful and tangible. This story resonated deeply with me as it will for many of my first-born-off-the-croft-generation; those with native Gaelic-speaking parents who grew up with little of the language of our ancestors and the loss of something intrinsic to who we are.

However, "Far Inland" is much more than this. It's a universal story of human truths which will resonate with people of all backgrounds.

If you love, as I do, writers like Per Pettersen and Sjon who successfully mix magic with everyday, mindful detail like gutting a brown trout, preparing a fire, you will love Peter Urpeth. I savoured this book intensely and intend re-reading it many times along with 'Out Stealing Horses' and 'The Blue Fox' because the satisfaction of 'Far Inland' is deep and lovely in a similar way.

Sam Gilbert - Library Thing December 2008: 5+

Set in Glasgow and The Western Isles, Peter Urpeth’s first novel tells the story of a modern-day shaman, Sorley MacRath. It is beautifully written and intellectually exciting, but also moving and redemptive.

The writing stirs you in the way that northern landscapes and climate can stir you. It is intensely evocative of the wildernesses of north-west Scotland; and not just in the descriptions of weather and sea and mountains. Its language is sonorous and archaic, with "the billowed grandeur of Biblical Gaelic"; it is "ancient in its tone and melancholy", like Gaelic song. (The breathtaking "Ninth Stone" epitomises it.) As such, it is very effective at conveying the idea that island folk carry a legacy of hardship, suffering, and sorrow with them, even in contemporary times, and when they are far from home. Just like the crofters & fishermen who are his ancestors, Sorley's life is shaped by experiences of loss and violent death (often by drowning). The northern-ness of the language reaches beyond Scotland too: the grain of the Arctic north in Sorley and his kin, with their preference for the shielings out on "the moorland wilderness", Sorley's love of the Fir Chlis, and his attachment to the fox-piss-damaged Rasmussen volume underline this connection.

Its themes are intellectually stimulating too. There is much poetic exploration of big ideas like culture, ancestry, and time. On a number of occasions I was reminded of Eliot's line in Burnt Norton that "all time is eternally present" - like when Sorley takes a handful of silt from the pool and holds it "until it was again an ice flow, flowing from a glacier, far inland"; or when he is compared to "a salmon [running] back to its first home, the gravel bed, the river source"; or identified with An Sgarbh's "ruddy sail" as he walks out into the waves cursing Shony. The novel is full of stories-within-stories - most obviously in the Thirteen Stones section; but also in Danny's story, and Danny's story of Davy; and in the story of Sorley's great-grandfather the whaler and his second, Inuit family. The effect is to suggest that the underlying truth and meaning of human selfhood is connectedness to one's culture & ancestry, even when it is characterised by grief & pain: and as with Breabadair Diluain, turning away only defers & magnifies it.

It is also very interesting and moving on the subject of mental illness. Its "great sorrow", and its associated isolation and alienation are powerfully conveyed. But there is a duality as well: for Sorley, it brings "elation", even "ecstasy" and "euphoria"; and through it, he eventually finds himself, Neonach as he is. Fittingly, there is unresolved ambiguity over whether hie second-sight is 'real' or not. On the one hand, there is Sorley's drunken vision lying outside the pub under "woven plastic sacks...flecked with the remains of raw meat", a parody of the shaman’s calf-skin hide; but on the other, there is nothing to contradict the miraculous resurrections of Angus or Callum. ( )

samgilbert | Dec 9, 2008