Silent Movie Music

"But being silent, it needed accompaniment and for this festival-goers had a chance to experience again the real genius of artistic polymath Peter Urpeth." Events magazine

Pianist Peter Urpeth composes new scores and performs live to classic and rare silent movies.

In the last decade he has received seven major commissions for new scores to classic films, ranging from Nosferatu to The Passion of Joan of Arc and Nanook of The North.

These three films remain available as performances to cinemas, art venues and festivals.

Performances are possible in most spaces, the venue provides the screen, projector, film, I can provide my the piano and amplifier for the music, as well as in-venue introductions, as required.

Prices are reasonable, accessible, and for me, live music in the cinema is one of the best film-going experiences around…

An archive site with projects and reviews, featuring work up to January 2019, is available here

These films are currently available for festival performances and for cinemas and arts centres.

Nanook of the North

A new promo trailer for the new score and live performance by Peter Urpeth and Mark Hewins…

A full length accompaniment to O’Flaherty’s iconic Nanook of the North featuring original music and sampled Inuit songs. The score mixes live piano and live electro-acoustic elements to create authentic soundscapes and haunting melodic passages…

Fred Silver’s review in Events magazine:

A musical and cinematic ‘tour de force’ took place at An Lanntair on Saturday afternoon (November 5) as Faclan – the Hebridean Book Festival – took its regular excursion into the world of black-and-white film with the stunning documentary Nanook of the North.

This film is regarded as cinema’s first significant nonfiction feature, made long before the term “documentary” was coined.

It was filmed in the very early 1920s, based on even earlier work done on film more than 100 years ago, and yet its technique and style – despite the weather conditions of sub-zero northern Canada – were thoroughly modern and accessible.

Of course, it is a silent film – and to be honest, having been irritated beyond measure by documentary film commentaries over the years – I think we should go back to that format!

But being silent, it needed accompaniment and for this festival-goers had a chance to experience again the real genius of artistic polymath Peter Urpeth. The score was Peter’s fourth commission for An Lanntair for silent films, following Nosferatu (2011), Vampyr (2012) and The Passion of Joan of Arc (2014).

Festival director Roddy Murray said in his introduction to the event that Peter had put so much work and research into his commission for the 2014 event that he felt unable to touch a piano again for almost a year.

For Nanook Peter took the whole process a stage further – first, he was joined by renowned guitarist Mark Hewins and, second, the score included a huge range of electronic music and a wonderful selection of sounds which complemented the film so well that it was sometimes completely impossible to believe there was not a live soundtrack on the film.

Filmmaker Robert Flaherty lived among the Eskimos in Canada for many years as a prospector and explorer, and he shot some film footage of them on an informal basis before he decided to make a more formal record of their daily lives.

Financing was provided by Revillion Freres, a French fur company with an outpost on the shores of Hudson Bay. Filming took place between August 1920, and August 1921, mostly on the Ungava Peninsula of Hudson Bay.

Flaherty employed two recently developed gyroscope cameras that required minimum lubrication; these allowed him to tilt and pan for certain shots even in cold weather. He also set up equipment to develop and print his footage on location and show it in a makeshift theatre to his subjects. This development and printing was a complex chemical process requiring another kind of genius to succeed in these conditions – but it was essential in getting the people involved in the film to understand what was happening.

During his earlier filmmaking in 1913, Flaherty had lost almost all his film in a fire – and he had learned something all filmmakers learn – that is, you simply cannot record events as they happen because that makes a terrible film.

So for this film, Flaherty staged scenes – hunting for seals, arctic fox, walrus and fish; building an igloo; settling down to sleep at night; and children playing in the snow – to carry along his narrative. The film’s tremendous success at the time confirmed Flaherty’s status as a first-rate storyteller and keen observer in the harshest environmental conditions. Sadly, Nanook, the top hunter and the subject of the film, died of starvation while hunting deer a couple of years after the film’s release.

There were two or three moments when I got totally lost in the film – one was right at the end when I was right there in the igloo, sheltering under the skins, the air around sub-zero to avoid the igloo melting, and everyone – human or dog – asleep or waiting hopefully for morning as a relentless storm raged outside.

Another wonderful moment was during a scene where white traders at a nearly trading post were playing a gramophone recording for the visiting Inuit – I found myself thinking that Peter’s music was over-riding the sound of the crackle of the record and sound of the voice singing…when, of course, he was providing the sounds!

The film vividly showed a society that was entirely transitory and in conflict – the landscape of ice and sea, wind and snow, changed constantly; the built environment was entirely impermanent being made of ice; the sledge had to be protected at night from the sled dogs otherwise they would eat the sealskin ties that bound it together, dooming the little family; the puppies had to be confined in a mini-igloo all night lest the older dogs ate them; the children played with ice sculptures; even the igloo’s window was made of ice; and between hunting and sleeping, there was just time to eat and snuggle down together.

I had heard of Nanook of the North (Nanook means polar bear) but I never imagined the film was so amazing and challenging…not would it have been without the extraordinary work of Peter Urpeth and Mark Hewins – I hope very much this was recorded by someone, otherwise our own transitory age will have lost a gem.

Mark Hewins is a British jazz guitarist whose professional career began in 1970 and who has been involved with a host of musicians in the UK and US – he was Lou Reed’s guitar tech on several tours. In more recent times he was on the Elton Dean Quartet’s Sea of Infinity and he has played guitar with Bob Geldof.”

The 2016 Falcon Festival Trailer…

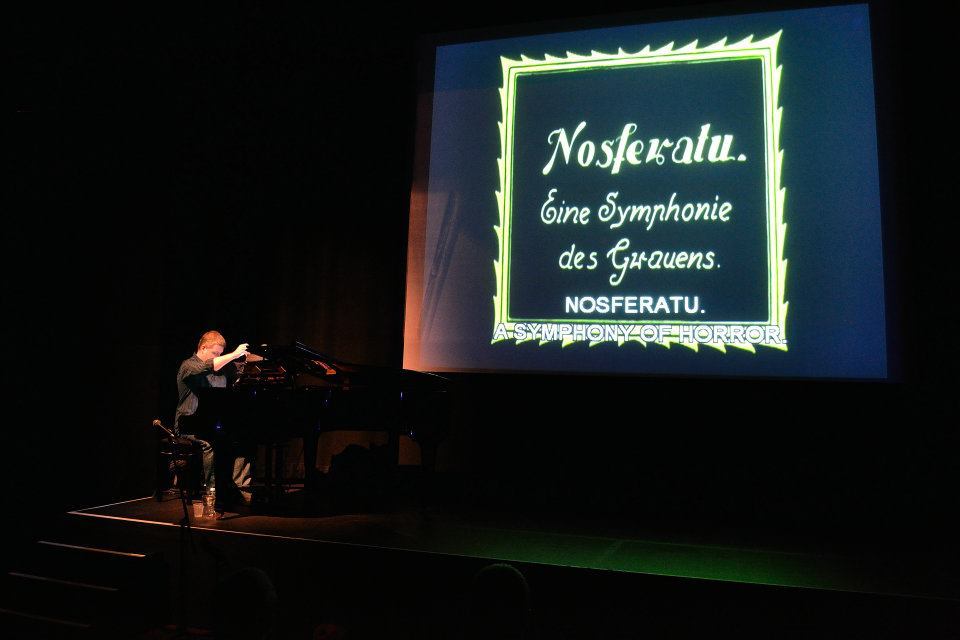

Nosferatu

Nosferatu - A Symphony of Horror (Murneau, 1922)

A new score for the timeless classic.

This film is suitable for all programmes, but especially for those dark winter evenings, Halloween and when the best horror movie made in the silent movie is the only thing good enough for a truly class event.